There's a version of this essay that's about doing things that don't scale as a growth tactic. You've read it. I've read it. The idea is that you do the unscalable thing early like the handwritten notes, the personal onboarding calls, and then once it works, you systematize it and move on.

This isn't that essay.

This is about the things you do that actively resist scaling. The things that get more expensive, more inconvenient, and more irrational the bigger you get. And the argument isn't that you should do them anyway as some temporary phase. It's that protecting them might be the whole point.

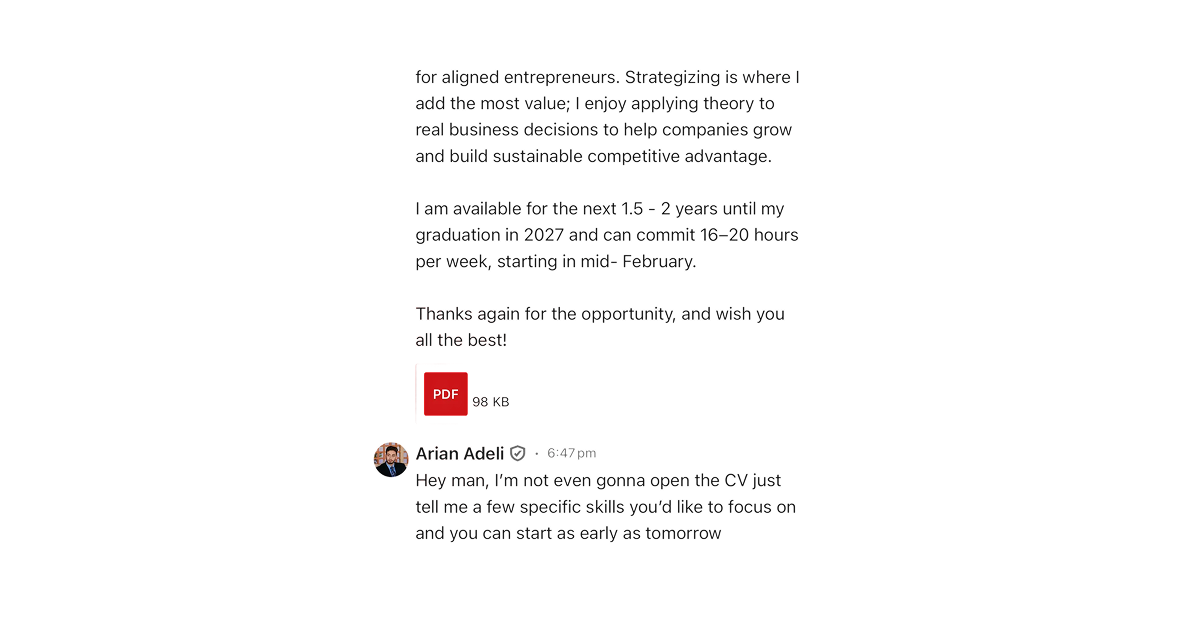

I still respond to most messages that come my way. Not the cold, cold pitches, but if someone took the time to write something real, I take the time to read it. I take meetings when people ask, especially if they're younger and clearly just trying to get a foot somewhere. I know I can't do this forever. But some of my closest collaborators came through exactly those conversations, and so did many of our hires.

My first hire happened because I accidentally answered an email while on vacation. A kid my age had reached out about a junior marketing position and I responded almost by reflex. We were supposed to meet and I stood him up because I couldn't figure out the schedule. I still feel terrible. I spent the rest of the day convinced I'd tell him I wasn't in a position to bring anyone on. We got on a call the day after and that's exactly what I said. He told me he wanted to work with us anyway, for free, despite having other paid offers on the table. He said what he saw in me was closer to the life he wanted to live than what he saw in his other interviews.

I said the hell with it, let's do it.

That night I thought I'd made a mistake. I woke up the next morning and I was a different person. Not because he turned out to be talented, though he did. Because the weight of being responsible for someone else's bet on you is the kind of thing that rearranges your priorities overnight. That feeling still carries me.

None of that was supposed to happen. An accidental email, a missed meeting, a conversation I tried to end before it started. One of the best things that came out of building this company arrived through a door I was actively trying to close.

There's a popular framework in scaling companies. You figure out what works, you systematize it, and then you remove yourself from it. And for most operational things, that's correct. You can't personally pack every order. You shouldn't be the only person who knows how the billing system works.

But somewhere along the way, this logic leaks into places it doesn't belong. It starts touching the things that aren't operational at all. The things that are, for lack of a better word, constitutional. The choices that define what kind of company you actually are.

The distinction matters. Operational things are how you deliver. Constitutional things are why anyone should care. And the problem is they don't come with labels. Nobody walks into a meeting and says "this is the thing that contains our soul, let's be careful with it." It usually looks like an inefficiency. It looks like something a consultant would flag.

When we were designing our logo, we brought in a prominent designer to realize our vision. We'd already spent countless days and nights in-house brainstorming concepts before bringing him in. He produced round after round of work. In his many years in the industry, he told us he'd never done so many revisions and concepts on a single job. It took so long that at some point he stopped caring about the increased pay. He was genuinely worried his work might never get used.

We ended up naming the icon The River, after the Springsteen song, because it was on repeat the entire time.

We finalized a concept and spent several more days refining it in-house. About two months later, I had a random light-bulb moment on a Saturday, immediately put together a draft, and rebranded all over again by Monday.

Was all that rational? Not by any standard measure. Believe me, I'm the last person to procrastinate on a logo before figuring out the offering. Evernomic didn't even have an updated website for the first three years of our journey because I didn't want a "Look! We're great." page. So when we rolled out our brand publicly, it had to be something that deserved to attach itself to our work. Even then I was initially planning to go with something low-effort, but it was my closest friend who reminded me "your work deserves better."

Do I regret all the back and forth? No. It wasn't about reaching perfection. It was about having no doubts. We needed to explore every concept just to scratch the itch and not leave any stones unturned.

Nobody will ever look at that logo and understand what went into it. That's fine. The point wasn't to produce something that screams effort. The point was to make a decision we could live inside of.

Saying no is the other half of this, and it's the half I still often struggle with.

There was an opportunity that came up that was genuinely good. Not a bad deal with bad people — the opposite. Everything about it was right on paper. But it required my time personally, and I had commitments to my team that needed that time instead. So I turned it down.

That's a boring story. There's no villain, no red flag, no dramatic walkout. But I think the boring version is actually the more common and more important one. Most of the decisions that define a company aren't choices between good and bad. They're choices between good and good, where the difference is what you've already promised and to whom. The discipline is in honoring commitments that nobody would blame you for breaking.

Here's what I think actually happens to most companies. They don't sell out in some dramatic moment. They just optimize, one reasonable decision at a time. Each decision makes sense in isolation. Automate this. Delegate that. Outsource this other thing. And slowly, without anyone noticing, the company becomes a perfectly efficient machine that produces something nobody has any particular feeling about.

The things that made it worth caring about weren't features or processes. They were choices. Small, specific, often expensive choices, about what kind of place this would be and what kind of people would build it. Those choices are the first things to go when the spreadsheet starts talking.

We've made a lot of hires on character. Not exclusively, but meaningfully. The designer I mentioned before — one of the reasons we brought him on was that I texted him at 2:30 in the morning and he responded within the same minute. He started on our first concept the next morning. Days later he was at a bar and still brainstorming with me. I liked that. Not because I expect people to be available at 2:30AM, but because it told me something about how he related to work. It wasn't a job to him. It was a thing he was in.

We're not a company in the traditional sense of people who happen to work at the same place. We're closer to a family. We care deeply, we're extremely close, and the work isn't something we do just because it's our job. That's not a recruitment pitch. It's a description of something that exists because we've protected it, actively, against the pressure to professionalize it into something more manageable.

So here's what I'd actually suggest, not as advice but as a exercise worth doing.

Map out the things in your company that are expensive, slow, or irrational. The things a smart advisor would tell you to fix. Then ask yourself: which of these are operational inefficiencies, and which are constitutional choices?

Operational inefficiencies should be fixed. If you're manually doing something that a system could do better, fix it. Don't romanticize friction.

But constitutional choices like the way you hire, the way you treat people's time, the quality threshold you refuse to lower, the deals you walk away from, those need protection. Not because they're efficient. Because they're the reason you're building this thing and not something else.

The discipline isn't in scaling. Everyone scales. The discipline is in knowing what to refuse to scale, and having the nerve to protect it when the numbers start suggesting you shouldn't.

That's the stuff that compounds. Not into revenue, necessarily. Into identity. Into the kind of place where someone texts you at 2:30AM not because they have to, but because they're in it with you. You can't scale that. You can only decide not to destroy it.